Reading time: 14 – 16 minutes, by: Hugo Pilate & Yuri van Bergen

The gaming industry has seen an incredible boost over the past 20 years. This growing appetite for digital experiences has also led to the diversification of what falls under the increasingly fluid category of “video games.” Outside of the typical gunning, e-sports, or strategy games, formats like walking simulators and vast open world games have emerged that demand very different commitments from their players

Although the connection may not seem so evident at first, there is much to learn from the world of gaming (the games themselves but also the player communities that have grown around them) when thinking of radically reducing the carbon footprint of the housing stock and other renovation strategies. Especially when trying to identify innovative means of improving the liveability of our cities or coping with (energy) poverty. Gamers are regularly challenged to rally other players behind a common cause, to take part in meticulous inventory management and optimization. But also to project themselves, imagining the repercussions of their decisions in varying scenarios.

So why write an extensive article on ‘How can gaming culture challenge social design and home renovation?’ For that answer we have to go back a few decades in time.

The neighbourhood in control of there own houses

In the eighties -before the internet became the fuel for modern gaming- the invention of renovation with tenants began. If you try to compare this with how things are done today you’d have a tough time. You really had to be there to understand the difference. Perhaps a comparison with the world before and after the introduction of the mobile telephone is a good example. In the ’80s it wasn’t common for people living in rental houses to have any influence of any kind on the quality of their neighbourhood and home. The owners and government decided what was best for you (and them). For example when the city of Amsterdam decided to build a new metro line through the city requiring whole areas of houses and people to move for this construction, it led to a national protest. In that time there was an all or nothing policy with no position or voice for the people actually living there. In those days there were experts who supported the people living there by making alternative plans that most of the times where better for all parties involved. Later on came the problem that these experts became too expensive because of the demand of plans to be developed for the people living there. Since they were tenants and not professional developers this first wave of participation in neighbourhoods became less popular due to the lack of funds available to support this kind of resource-intensive local planning. One of the solutions was to get the social housing corporations to pay the bills of these experts. Although at first this was a good and functional solution, the people who lived there started to lose their influence on the plans and thus the control over their own neighbourhood.

So let’s jump back forward in time. Today 70% of the housing population is owned by private house owners. These houses are spread across 14 thousand neighbourhoods throughout the whole country. To successfully reduce their carbon footprint they have to organize themselves as a neighbourhood when making plans to renovate their own house. And we all know this is not easy when everybody has their own ideas to add on how it is ought to be done . So again why write an story about the idea how gaming culture challenge social design and housing renovation? Because we think that you’d be surprised how many possible answers the gaming world has to offer for each of these problems. Let’s explore a few.

Scenarios and Role Playing

Perhaps the first game that comes to mind when thinking of city-making and renovations are the Sims and SimCity games. Since their appearance many other games have followed in their footsteps offering different ways of simulating urban activity. The documentary Gaming the Real World offers an interesting outlook on how very different games can each inform how we think of the city and neighbourhoods in very distinct ways: some focus on recreating with high fidelity the ebbs and flow of urban life, often referred to as “digital twins” while others try to offer new kinds of cities all together.

When thinking of computer-aided city simulation, there are several types of games or virtual tools that can be used. These are not “official” categories nor are they mutually exclusive but they help capturing the core intent of each game / tool:

- Interactive render: These are the static virtual 3D renditions of cities, more like architectural models, abstractions, rather than getting to the systemic complexity of the city they offer a limited understanding of what is at stake. One such example is this 360 rendition of an upcoming development in Eindhoven or this more narrative-driven showcase of the Schoon Schip in Amsterdam. Sadly these are often presented as “immersive” but I find that to be a misnomer since a central part of immersion is the interaction ability of the environment which they often lack.

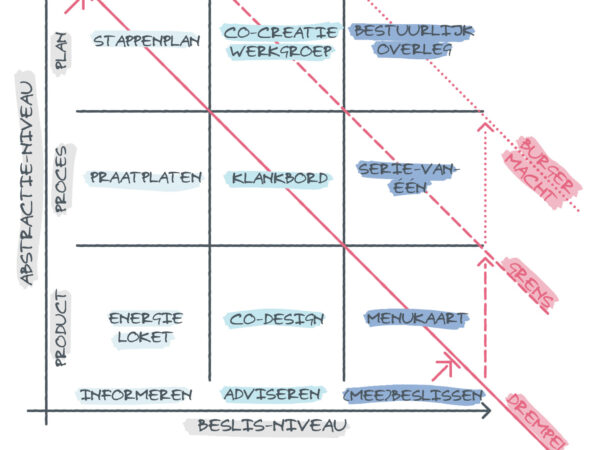

- Scenario simulator: A great example of this is the City Skylines video game which allows for very detailed recreation of urban environments and how new developments might affect the mobility, energy consumption, and pollution generated by the area. Of course simulators are great for understanding how one scenario might “play out” compared to another, but another interesting application is how they can also provide a fun and incremental way to learn about a complex topic with many moving parts. The Kerbal Space Program game for instance uses very accurate physics simulations that challenge the players to dive into the complexities of physics, costs, and propulsion mechanisms.

- Parametric iterator: Iteration in the design process often happens on paper early in the project or during the production phase when things don’t go according to plan and new solutions need to be found. However, more and more game-inspired tools are exploring how iteration can be automated through parametric approaches: setting certain parameters and letting the program offer up solutions. One game that has popularized this practice is No Man’s Sky back in 2016, showing how nearly infinite planet permutations could be created in a game environment. Today architects and urban planners are playing with such tools to test new design solutions. Two striking examples are the Procedural Liveability Project and Block’hood. Both offer more or less interactive means of trying out city making “recipes” and figuring out what works and what doesn’t as you go.

- Cost calculator: Weighing the trade-offs of different solutions is at the heart of many games, so it’s safe to say that this last format is often used in conjunction with another. However it is also one of the more common “participatory” software used in urban development if you think of platforms like Giraffe app or MIT Media Lab’s Solar Cities. These tools allow groups of stakeholders to collectively evaluate the relevance of different design solutions according to a range of predefined metrics: traffic congestion, monetary development cost, or sunlight distribution. What’s most interesting about “cost calculation” in games is that the definition of cost gets stretched a bit. Sometimes the cost is translated into units of a certain material like wood and other resources in Age of Empires or in the time something will take to build. Some games will take this further into fuzzier costs, strategy games like the CIV series will offer metrics like “citizen (un)happiness” that would be difficult to integrate in a real world situation. However, this kind of open-ended thinking about “what to measure” is crucial in our society of mass cost-cutting and optimization. One striking example of rethinking cost estimation to encourage the adoption of more restorative or circular practices in cities is Dark Matter Lab’s piece on trees as infrastructure where they highlight projects like i-tree trying to capture the far reaching impact of a healthy (and long term) tree and vegetation strategy in NYC.

Crafting and Inventory management

Crafting and building contraptions is present in all sorts of games like World of Warcraft, Call of Duty, Little Big Planet, Minecraft. These will depend on predetermined recipes whose ingredients or components have to be scavenged to then craft the desired object. Perhaps the fact that such game mechanics exists isn’t so surprising if seen as a means of having a “more powerful” character and outperforming others, but it has increasingly become a form of playful exploration, bordering on alchemy, which requires patience, attention to detail, and focus.

This appetite for crafting and the seeking, collecting, and optimizing of the parts required for crafting can lead to very interesting possibilities for the world of restoration and fabrication at large. How can this interest in exploratory making be channelled to renovate our cities? A couple strategies come to mind:

- De-risking: Repair and maintenance work is rarely seen as being “exploratory” in the physical world. The aim of most repair missions is to “restore” the object in question to a functioning state, often leading to buying a new one to replace it instead of risking trying to fix it. What games offer is a place to try things, see what works and what doesn’t without risking a house fire, being late for work, or any other dangerous situation. One great example of de-risked experimentation in games is in modding communities like Grand Theft Auto (GTA) or Half Life’s Garry’s Mod. These games have been designed by their developers to be modded, or repurposed, by their players allowing them to make new objects, maps, or even scripts. You also have games that may not allow modding but have been designed as sandbox environments, where building is at the heart of the gameplay like Besiege. So how can derisking be made possible in the renovation space? Is it through virtual assembly simulations? Risk-free crafting experiences? Is it by working one on one with trained professionals?

- Immediate Feedback: The other aspect of gaming that makes crafting in virtual worlds especially interesting is simply how quickly you get feedback on your creation and how clear that feedback is: it worked or it didn’t. This may not seem like much but in a culture of convenience and retail therapy, getting reassured you’ve “done it right” is a crucial step of any user experience, which makes buying a “new” thing the easiest way to feel like getting it right. Feedback can either be prescriptive: here is a recipe, follow it as found – in Minecraft, or more open ended like the game Block’hood mentioned above where you are challenged to craft a sustainable neighbourhood guided by best practices but never with a precise recipe.

- Unprecedented scale: Lastly, games allow players to impact their environment at scales that are incomparable to that of the physical world: shape civilizations, cities, generations. By managing a city, or civilization, you get to watch it evolve and understand the impact of your decisions. Even in games presented from one character’s lifetime like Red Dead Redemption, how you groom your horse, how you acquire the money to buy new horses, how you feed them, informs how well equipped you will be to explore the game having a very real impact on your sense of self and preparedness to face the adventures ahead of you without making it explicitly about defeating others. Over the years, game developers have learned to find unique ways for the players to leave an imprint on their game environment, saying “I was here”. Game environments can help makers, builders, home owners, better understand, better feel, the impact of their decisions by visualizing hidden forces, impacts, of their projects. For instance they could turn into actual game mechanics the reduction of one‘s carbon footprint. But beyond creating high-end carbon footprint calculators, could game-based incentives motivate individuals to get out, mobilize, and organize? Niantic, known for Ingress and Pokémon Go have been championing this field of Mixed Reality and using physical space as an integral part of their gameplay but using the virtual space to give the impression of a greater calling. So what could a Pokemon Go + Read Dead Herbal Recipe + DIY home improvement planner game look like?

Image 2. Cityskyline reddit.

Community building

Gaming communities come in many shapes and forms, whether it is fans of upcoming games following the early-stage development of a game on Discord, couples meeting on World of Warcraft, or informal wikis to figure out the best ways to make their way through a level, the virtual spaces in which these take place have very real social networking implications. Through these activities, players get to collaboratively solve problems, prioritize needs, and work toward a collective goal motivated by the love of a game or its world.

Now imagine if this kind of engagement could be harnessed to renovate our neighbourhoods… Where different households would try different products and tell each other about them, where some could easily try out their neighbour’s hacks? Where a few neighbours come together to help each other when a build is very labour intensive? Of course, anyone can find a YouTube tutorial, but how can this process be made into a community building exercise like the many Minecraft maps that have taken groups of players years to build?

Here are several strategies that can be adopted from gaming culture:

- Community fostering: Shared platforms for the exchange and sharing of content, best practices, but also the celebration of unique talents as done on Twitch, Discord, YouTube.

- Cooperative game settings: One very direct example is rePair which challenges pairs of players to fix a product together in a limited amount of time.

- Behind the scenes: The gaming sector at large is a world where the game and the making of the game are regularly blurred, there is a strong appetite for testing and debugging together which can be one way of derisking new experiments while fostering interest around emerging solutions.

- Opting-out: That being said, it is of course much easier to turn off a computer than to “disconnect” from your neighbourhood, this kind of very involved shared development should be made easy to opt out of for those who are not as into it as they hoped.

Image 3. TerraNil.

Alternative narratives

Outside of the more utilitarian inspirations to be drawn from the gaming world, there is also an increasing diversification of genres and narratives being offered in the gaming world, including games on renovation, making, and repair. Two games that come to mind are Common’hood and Terra Nil:

- Common’hood: The game gives its players the opportunity to run their own makerspace. Designed to take the player in a couple hours through an experience that would otherwise take years or incredible funds it helps broaden our imagination of what a makerspace could be and what its role could be for the surrounding community.

- TerraNil: Designed to expose players to regenerative practices, the game offers puzzles in which players have to restore wastelands into lush biodiverse environments. At the end of each level before repurposing the technologies they used to make a spaceship that leaves the restored wasteland. This game premise could easily be revisited to imagine “renovation crews” that come in and work with neighbourhoods to reduce their footprint and improve their liveability.

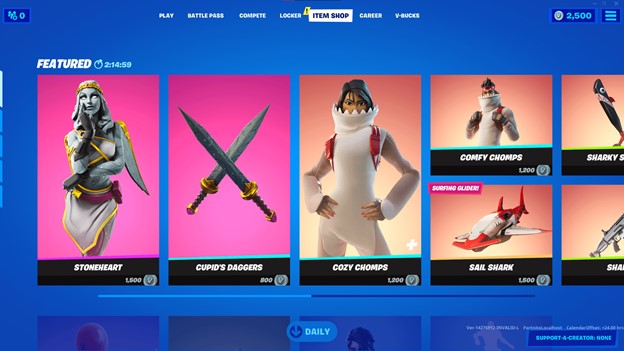

Image 4. Fortnite store.

Platform economy

Perhaps one of the most disruptive transformations in the gaming sector is the shift towards games that keep growing or evolving. Similar to streaming and other on-demand platform-based services like Netflix, many games have crafted new business models around the seasonal release of new materials. The best known example of this is Fortnite, which offers new skins and content available in their online store at any point of the game. The gaming industry always had patches and expansion packs but here, the updates are far more regular and central to the business model (and available for impulse buys in the middle of the night). This means the game itself, again like Fortnite or Netflix, can be made available for free (becoming a marketplace) and the digital content becomes the core of the business model, like a streaming platform.

Can this kind of platform-based logic help make renovation projects more accessible? Can there be a small fee raised by a neighbourhood that allows for technicians to be on retainer? How can this type of approach be used to encourage repair and not just the purchase of new parts as Amazon does?

Conclusion

This article is meant to openly share the possibilities our team found when exploring the way gaming could reform the rethinking of the renovation sector. It is not a market analysis on gamification trends but an invitation to collaborate and explore this uncharted territory. That being said, we are fully aware of the challenges, not to say dangers, of digitizing just for the sake of innovation, especially when working with individuals’ homes. To be honest we’re not the person to give judgement about what’s right in this world or not. And that is not our goal or purpose of this article. Our goal is to inspire and initiate new relationships between service providers and homeowners and ensure that neighbourhoods have a voice that can be heard as a collective. Because at the end of the day, they are the ones who actually live there. So why not give them a (digital) platform to speak out every day, even when they are not sure what to say about all these complex social themes and sustainable goals?